Background

We have all seen the studies and even experienced first-hand the value of personalization in direct mail and other forms of communication. But what about the value of personalization in products and packaging? There are a lot of projections into what the market value ‘could be’. For example, according to a 2017 study the expected value of the personalized gift market will increase 55% from 2016 to 2021 to an estimated value of $31B. Another study from Deloitte estimates that 50% of Millennial and GenZ consumers express a desire for personalized products, and 70% of shoppers are willing to pay a premium of 10%+ for personalized products.

In the world of consumer packaging, the leading brands and CPGs are just scratching the surface of what is possible. Products can be localized to appeal to a specific target group, e.g. Philadelphia Eagles fans, or they can be individually customized with family photos and other personal information. This is all great news, but how do you, as a provider of print services, take advantage of it? Digital printing technology to support personalization has been available for a while, and new technology is being released regularly, but is it up to the task for today and tomorrow?

Variable data printing (VDP) has been around for decades, in fact it is the core technology for transactional print. The first generation of VDP tools were standalone software products accessed on a workstation or web portal to create variable graphic files for printing. The second generation of VDP solutions moved the variable data integration from prepress to the DFE. In the case of most transactional and even direct mail VDP, the variable data is applied against a template and fed as a data stream to the digital press’s DFE to apply the variable data into the print stream. However, the demands of variable data print for packaging are now exceeding the capabilities of transactional print solutions. As the requirements for variable data in packaging have changed to support variable imagery and graphics in addition to text, newer solutions needed to be developed to take the load off the DFE and bring it back to the prepress department to avoid slowing down the expensive digital presses.

The heart of any digital production workflow is the DFE (Digital Front End). It is the technology that processes and rasterizes the design file for imaging. DFE’s have been around long before digital presses, in fact that is what drove filmsetters and still drives platesetters. At the heart of the DFE is an interpreter that processes the images, fonts, colors, and other embedded file information and then rasterizes it for imaging on the output device. While the older interpreter technology at the core of the DFE was based on Postscript, the newer DFE’s are all based on PDF rendering technology. As digital presses became faster and designs became more complex, using the DFE to process variable data wasn’t as efficient, so there was a search for new next generation ways to address the needs of VDP production for today and tomorrow.

Changing Packaging and Label Requirements

Digital label and packaging production is on the minds of a lot of equipment vendors and print service providers today. This is primarily due to the potential opportunities driven by evolving market demands. According to the recent Emerging Technologies for Packaging Innovation study, published by the Graphic Communication Institute at Cal Poly, there is good reason for this.

According to the report, “CPGs (Consumer Product Groups) show no sign of letting up on SKU proliferation, thus exacerbating the impact of short runs on the supply chain. A quest for more product variations, sizes, tailored messaging, and promotions were all indicated as key drivers behind SKU proliferation. … CPGs also show a solid understanding of the impact of SKU proliferation on converters, the technology they use, and seek-out those that can offer a competitive edge with new technology.” In fact, the report continues, “71 percent of CPGs responded they actively seek converters/printers with emerging printing capabilities, such as digital printing.”

However, all of those involved in the packaging supply chain understand that there are challenges. Converters admit to “faster time-to-market requirements by CPGs placing stress on the existing infrastructure. … One hurdle to digital adoption is how fast print manufacturers can help CPGs approve the transition to new print processes for each and every material/packaging application. Nearly 85 percent agree that when moving from traditional methods of printing to digital, re-approval of all packaging will be required. This is an area of opportunity that technology and service providers will need to address.”

Adding to that challenge is that labels and packaging today increasingly requires the production of products in multiple versions. Those can include multiple language versions, targeted messaging to disparate consumer groups, products that are sold in a variety of color choices (e.g., beauty products), etc. The design tools used to create these, like Adobe Illustrator, were developed to use layers to enable the designer to work on the consistent base artwork with layers to support the versioning. This eliminates the need to use a single file for each version, especially since there are usually corrections up to the time of print on the base design as well as the versions. The design tools and review processes are fairly standard, but as an approved design moves into production new tools are needed to ensure good quality output, especially with the introduction of variable data.

Enter PDF 2.0

In the rush to facilitate the changes and the new speed to market needed for production packaging processes, PDF showed some early promise, although the available solutions were, and currently are, workflows that are proprietary to each vendor. In 2003, the Ghent Work Group (GWG) began working on the use of PDF and the surrounding best practices required for packaging production. These included special color handling; support for multiple versions, languages and roles; and specifications for an extensive range of finishing requirements. The goal of this work was to create a single

‘exchangeable standard’ PDF file that could be used for the communication of design, regulatory, and production information in one file for all types of packaging print production, including gravure, flexographic, offset and digital print.

Using PDF as the format for addressing the needs of packaging production has significant benefit. Once a designer’s work is finished, the processes of circulating the file for approvals, changes, prepress, die creation, etc., are now handled in a variety of non-standard ways. Using a linear process gives content owners and producers the security of having only one iteration of a file to work its way through that pipeline.

PDF 2.0 is the first new version of PDF since 2008 and was designed to address many of the new requirements dictated by wider adoption of PDF digital file distribution as well as specific use requirements like those of packaging production. While not all of the new features in PDF 2.0 impact print production, some of them do and are supported by Adobe PDF Print Engine (APPE) 5 and the Harlequin Host Renderer, the primary core processing engines in modern DFE’s. PDF/X is the print specific standard developed on top of PDF to ensure successful blind exchange of design and production files. PDF/X-6, the next version of that standard, is currently in development and will be based on PDF 2.0. In fact, PDF 2.0 and next generation software that can take advantage of its features are now beginning to address many of those needs.

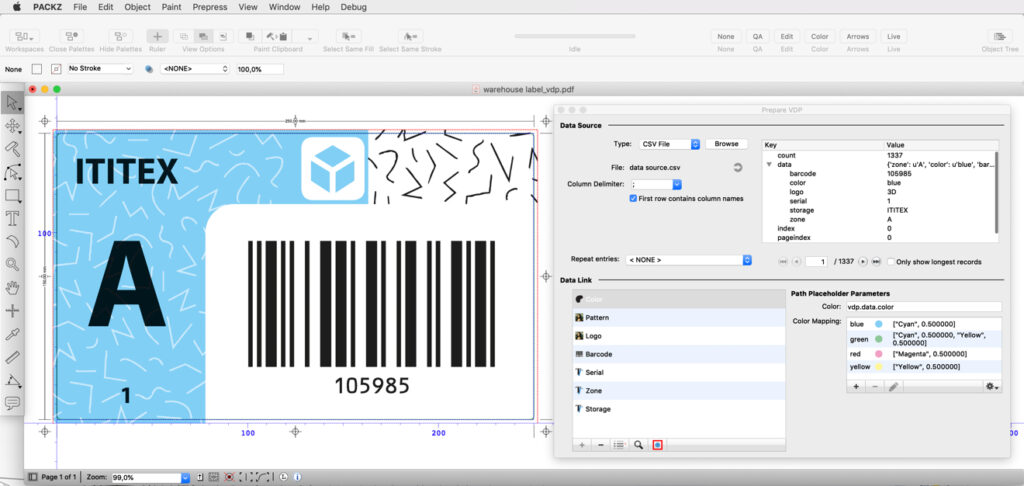

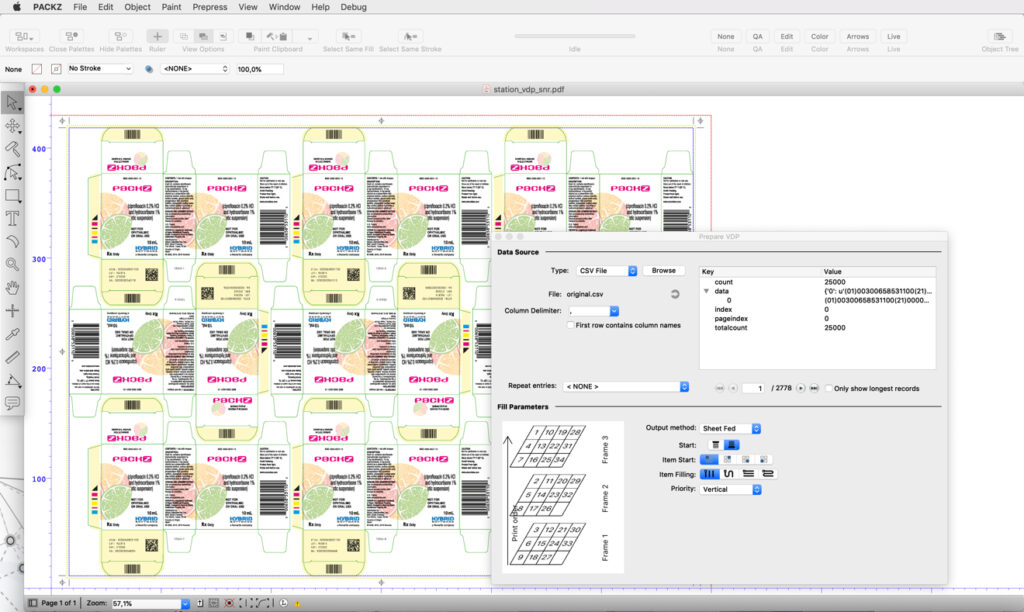

PDF is an object-based file format. With the right tools, each object in a PDF file can be edited independently without the need for the original native document creation software. Additionally, PDF 2.0 supports the ability to assign metadata to PDF objects. This means that with proper software tools you can assign variable data to a PDF object as well. There are a few PDF editing software packages in the market today, but currently there is only one, PACKZ VDP, that can support the addition of variable metadata to PDF objects and was designed specifically for packaging.

Converters that have moved to this new VDP processing workflow through the use of PACKZ VDP have been excited about the flexibility of the workflow as well as the speed. One of those is Ramon Pans Munne, the owner of cartonajes Pans s.a. in Barcelona, Spain. Their primary business is folding cartons for the pharmaceutical industry, usually as an imprint on the printed and die cut cartons. In 2016 they purchased an HP Indigo 7000 along with Esko ArtPro software. Their workflow was to import files to ArtPro’s internal format, then export them as PDF in order to use PACKZ and adopt a native PDF workflow for legacy jobs. This new capability has allowed them to address new markets as well. With the introduction of PACKZ VDP they are now creating small batches of folding cartons for cosmetics with store branding, with a simple change to the PDF file right in PACKZ.

Christophe Seguin is the General Manager of ELC étiquettes, a label converter focusing on cosmetics, and food, in Limoges, France. They have been offering VDP since they acquired their Xeikon 3030 press. Initially they were using the VDP solution included with the Xeikon DFE. Since using PACKZ VDP he has found that “it’s a lot simpler and quicker to setup the variable data to connect to the data source to the final print layout and then to generate the final file for printing”.

Advantage Label & Packaging, Inc. in Grand Rapids, Michigan had upgraded their equipment about a year and a half ago, and as part of that upgrade their new DFE included some VDP tools. Lauren Plinka, the Graphic Designer for Advantage shared some of their frustrations. “Unfortunately, there were many limitations. The software was not as user-friendly as we hoped and did not offer easy workarounds”. They found that characters within large fields had a tendency at times to drop out, causing errors. The templates were slow to RIP to the press, and the press operators still had to check to make sure our math in the manual set-ups was lined up correctly. It was not an efficient VDP workflow.

According to Plink, about 6 months ago, “almost by accident, we discovered that VDP Prepare was included in PACKZ. I opened one of our variable data jobs and, in just ten minutes, learned how to use it. It had already taken us a solid year to try to figure out our other software. It was so intuitive that almost immediately we asked for PACKZ VDP Execute. PACKZ can also be integrated with Hybrid Software CLOUDFLOW for an automated production workflow.”

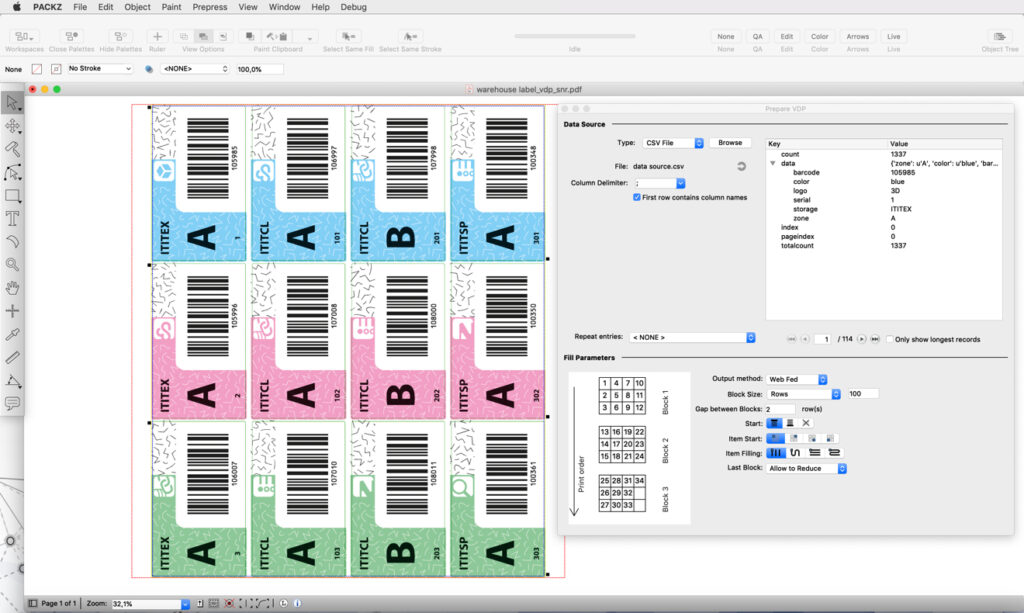

With PACKZ VDP, once the 1-up document has been linked to a dynamic data source, you can then define how to create the layout of each unique package in a step & repeat imposition. Should dynamic serialization flow left to right, right to left, or front to back? One click allows you to reverse the way numbered labels are wound. According to Plinka, “This might sound trite, but it makes a big difference when products are filled in a production line.”

Label and packaging printers are already finding an increase in VDP demand as a result of new mass customization and mass personalization requirements. Finding a reliable, easy to use VDP solution that can also be integrated into an automated workflow provides the ideal tool to address those requirements.